words you may not know

coal cracker

(US, slang) A native or established resident of the traditional coal-mining area of northeastern Pennsylvania; a worker in the mines of this region.

firedamp

Any flammable gas found in coal mines.

breaker boys

A coal mine worker whose job was to separate impurities from coal by hand in a coal breaker.

Coal mines across Appalachia were known for their output... and their shortcuts. From Kentucky hollows up through Pennsylvania’s northern fields, miners pushed tirelessly and risked their lives carving narrow tunnels while shaving costs on timber, ventilation, and safety. Inspectors came and went, but production always came first. In these environments, accidents were a matter of time, not by chance. In places like my hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, where coal created both wealth and poverty, miners like my great-great-great-grandfather lost their lives underground with little illusion about what waited for them in the dark.

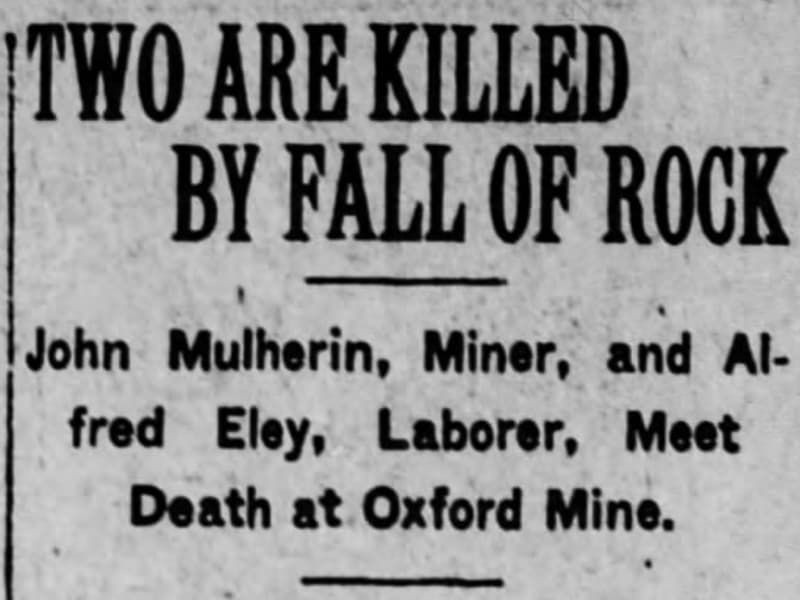

Newspaper Clipping #1

Caption: TWO ARE KILLED BY FALL OF ROCK - John Mulherin, Miner, and Alfred Eley, Laborer, Meet Death at Oxford Mine

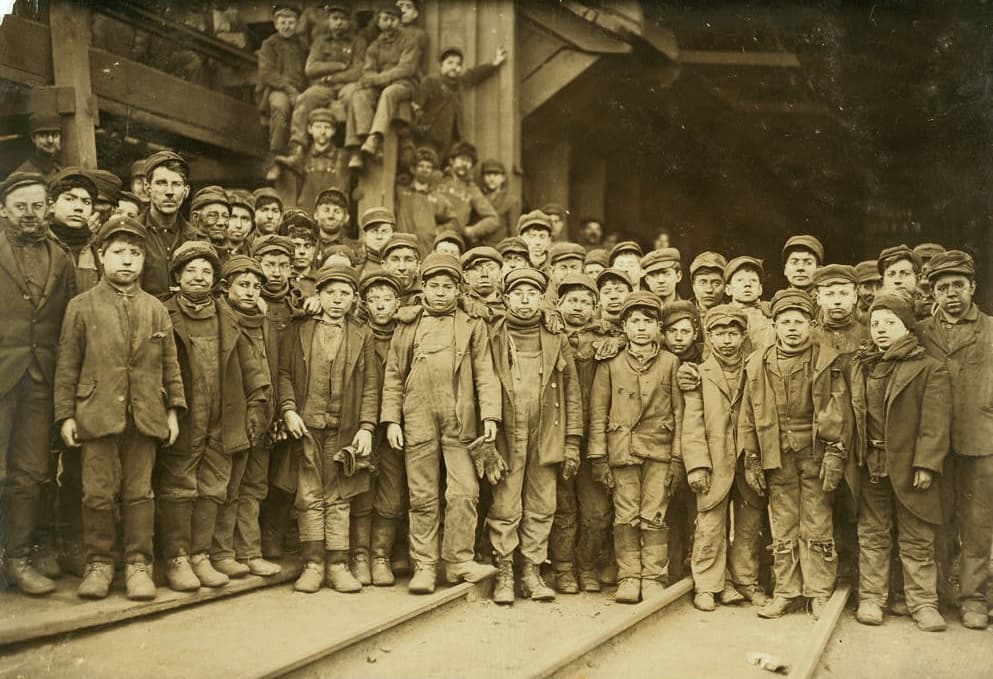

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Northeastern Pennsylvania (NEPA) coal was king. Coal mining offered a steady livelihood for impoverished immigrants from Europe, primarily Scots-Irish, Welsh, and Italians. The increasing demand for coal meant a reliable income: where there was coal, there was cash. NEPA’s specific coal variety, called anthracite, was especially valuable for its clean-burning properties that efficiently fueled New England’s industrial expansion. Even today, Northeastern Pennsylvania’s Coal Region remains the largest supply of anthracite ever found in the United States. Coal was a hot commodity, and opportunistic businessmen took advantage of this massive demand, setting up companies across coal-rich regions like Appalachia. Prior to the establishment of federal labor laws and mine safety regulations, these poorly educated immigrant populations were often exploited, working long hours in dangerous conditions for meager wages; their hopes for a better life were often overshadowed by the harsh realities of coal mining life. Child labor was fairly common in this setting, and young breaker boys were working as young as eight years old at the mines. Growing up in Scranton, the following image was embedded into our brains in grade school history class at a young age. It is a real challenge to live in Scranton and not hear about its industrial past.

Pittston's Breaker Boys in 1911

Breaker Boys working in Ewen Breaker of Pennsylvania Coal Co. in Pittston, PA, which is about 12 miles southwest of Scranton. This image comes from Lewis Hine’s collection documenting child labor across the United States. This work is often credited with leading to the passage of the nation’s first child-labor laws. Photographer/source: Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives.

If coal dust didn’t slowly choke miners with black lung decades later, the more immediate threats like roof collapses, firedamp explosions, and deadly shaft-falls, were still the greatest killers in Pennsylvania’s anthracite mines. When men came aboveground, there was little privacy from their employer, as their homes, general stores, and even Christian churches were often owned by the coal operation’s stakeholders. Miners would essentially tithe their wages back to the men who controlled their roof, rations, and, in effect, their fate: a devotion not to God, but to a profit-driven deity that was never heavenly but seemingly almighty.

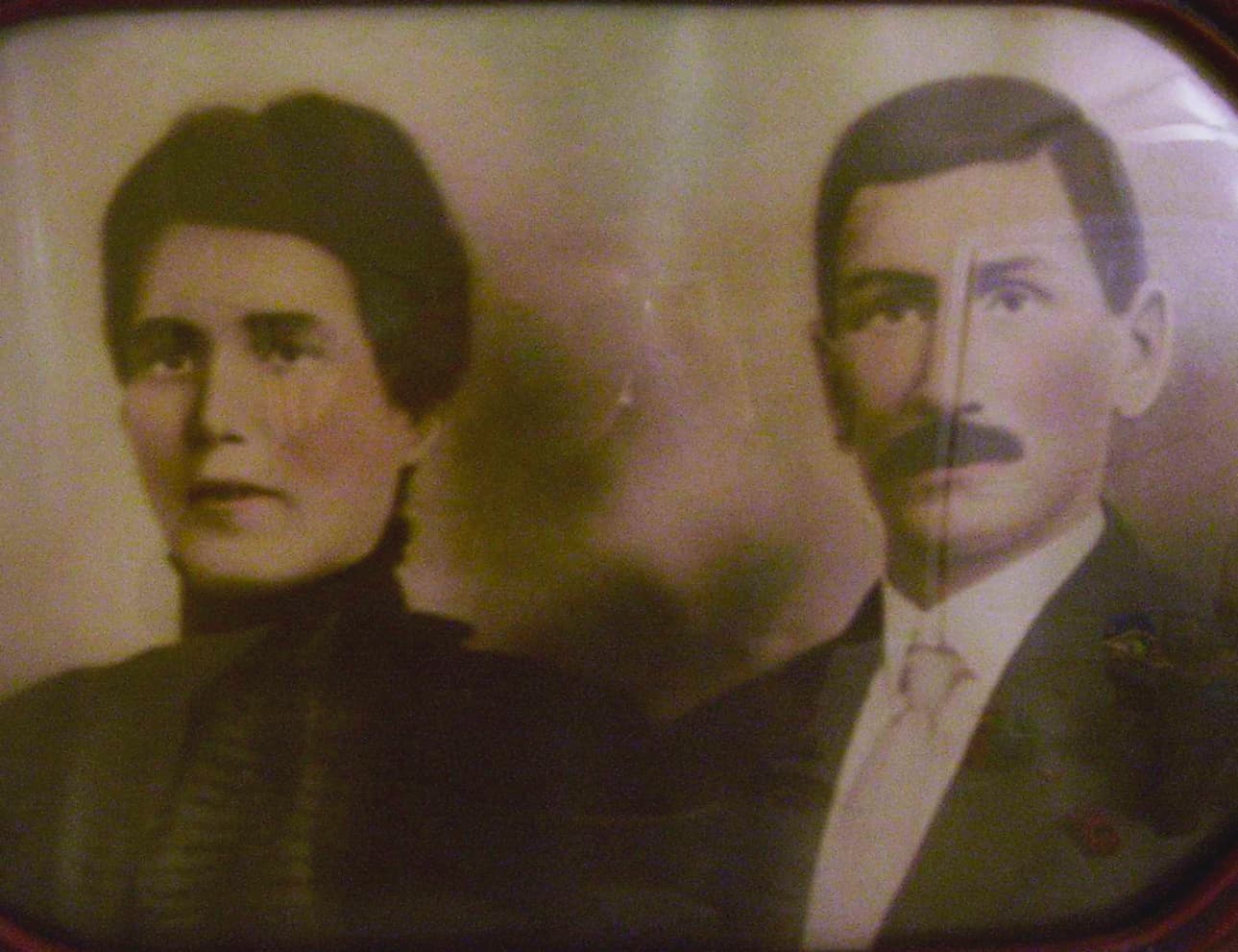

Introducing my Welsh great-great-great-grandfather, Alfred. I never met him because those are too many greats, but I have heard legends through family anecdotes passed down generations.

Alfred Eley and his wife, Julia, lived in a small row home rented from the People’s Coal Company in West Scranton, where he worked at the Oxford Mine. Eley worked as a laborer, not directly boring coal, but physically moving heavy minecarts and equipment. One day while working in the Oxford Mine, he and his boss, a miner, were “caught under a fall of rock [...] and were instantly killed,” according to a local newspaper. Eley’s “head was battered to a pulp,” and his coworker’s “body was badly crushed,” according to the article.

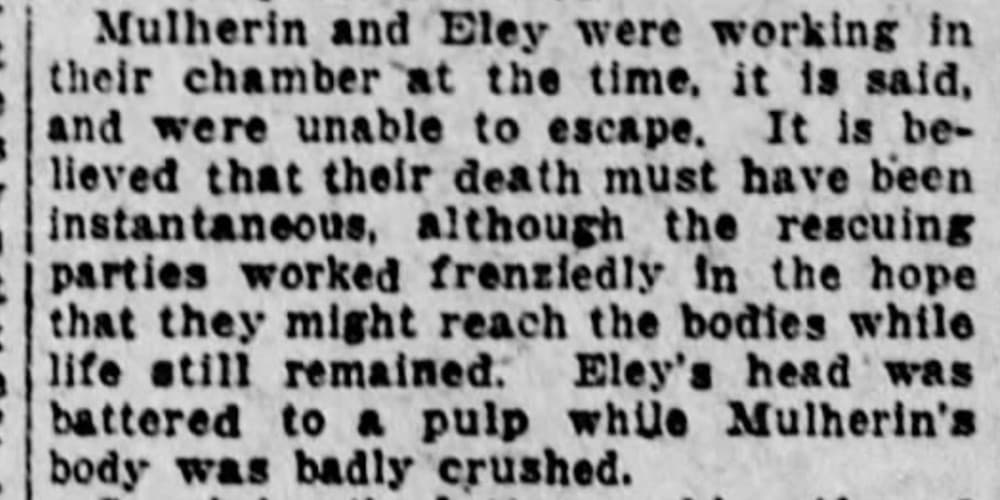

Newspaper Clipping #2

Caption: Mulherin and Eley were working in their chamber at the time, it is said, and were unable to escape. It is believed that their death must have been instantaneous, although the rescuing parties worked frenziedly in the hope that they might reach the bodies while life still remained. Eley's head was battered to a pulp while Mulherin's body was badly crushed.

In the years before Eley’s death, the Oxford Mine had already earned a reputation for pushing beyond safe limits. Since the 1910s, the mine had been under scrutiny for dangerously thin pillars and repeated cave-ins along North Main Avenue. Local engineers and civic leaders suspected that, in defiance of judicial injunctions, company officials were engaging in “pillar robbing,” the removal and subsequent resale of the very coal supports meant to hold up the roof. These business owners even went as far as to hide new coal mines behind hastily built walls to throw off inspectors. Tensions came to a head in 1920, when Scranton Mayor Alex T. Connell and a group of city engineers attempted to descend into the mine, only to be physically barred by armed company engineers. After a risky entry through an old secretive opening known as the “Cork and Bottle,” they documented extensive illegal mining and immediately secured a court order to halt operations. The ensuing “Battle of the Oxford” made national headlines, led to heavy fines (nearly $250,000!) and brief jail sentences for company owners and contracted engineers, but did little to prevent mining companies from committing crimes elsewhere.

During this period, coal companies demonstrated another appalling lack of humanity. Rather than allowing the family of the deceased to retrieve the body for proper burial, coal companies would hire undertakers that would unceremoniously drop lifeless bodies off on the victims’ own front porches, leaving the grief-stricken family to experience immediate horror and the subsequent task of arranging a burial. This was a symbolic message to let his now-widowed wife know she was no longer welcome in the company-owned dwelling. This was a quiet eviction notice, signaling that another family would be moving in, one capable of paying rent, sweeping the remnants of a household just destroyed by the coal industry off to the side. For the People’s Coal Company, the people were a commodity that could be quickly discarded and replaced. Soon after, Eley’s wife moved into her adult daughter Johanna’s home.

This often-forgotten piece of American labor history is a bleak reminder of what is always a possibility in the American workforce: you being deemed replaceable and becoming a product for some faceless company that promised to be for the people, devaluing the labor force it once championed. As artificial intelligence and automation penetrate fields once considered secure, we must remember that commercial obsolescence is closer than the opportunity to secure our futures before the market decides we have none.

In the anthracite fields of Northeastern Pennsylvania, miners once toiled under lantern light to feed a growing nation’s power needs. By 1917, at peak production, they were producing 100 million tons of coal, even as 581 men died that year alone hauling it up from the pits. Yet within a generation, cheaper oil and gas drove the region into a steep economic decline, and by 2010, underground output had fallen to a mere 207,000 tons after the Knox Mine flood of 1959 sealed King Coal’s fate.

Innovation drives both the birth and death of careers. Today, multiple sites within Northeastern Pennsylvania are being proposed as space for massive AI data centers. Monolithic digital breakers that promise jobs as they threaten to automate them away. And in a techy twist no one in the old mining towns could have foreseen, our current administration has officially declared an interest in powering these data mines with coal again, fueling talk of a 21st-century revival of an industry that younger generations had forgotten, but its legacies of disease, poverty, and blight still persist.

From The White House:

Our Nation’s beautiful clean coal resources will be critical to meeting the rise in electricity demand due to the resurgence of domestic manufacturing and the construction of artificial intelligence data processing centers. We must encourage and support our Nation’s coal industry to increase our energy supply, lower electricity costs, stabilize our grid, create high-paying jobs, support burgeoning industries, and assist our allies.

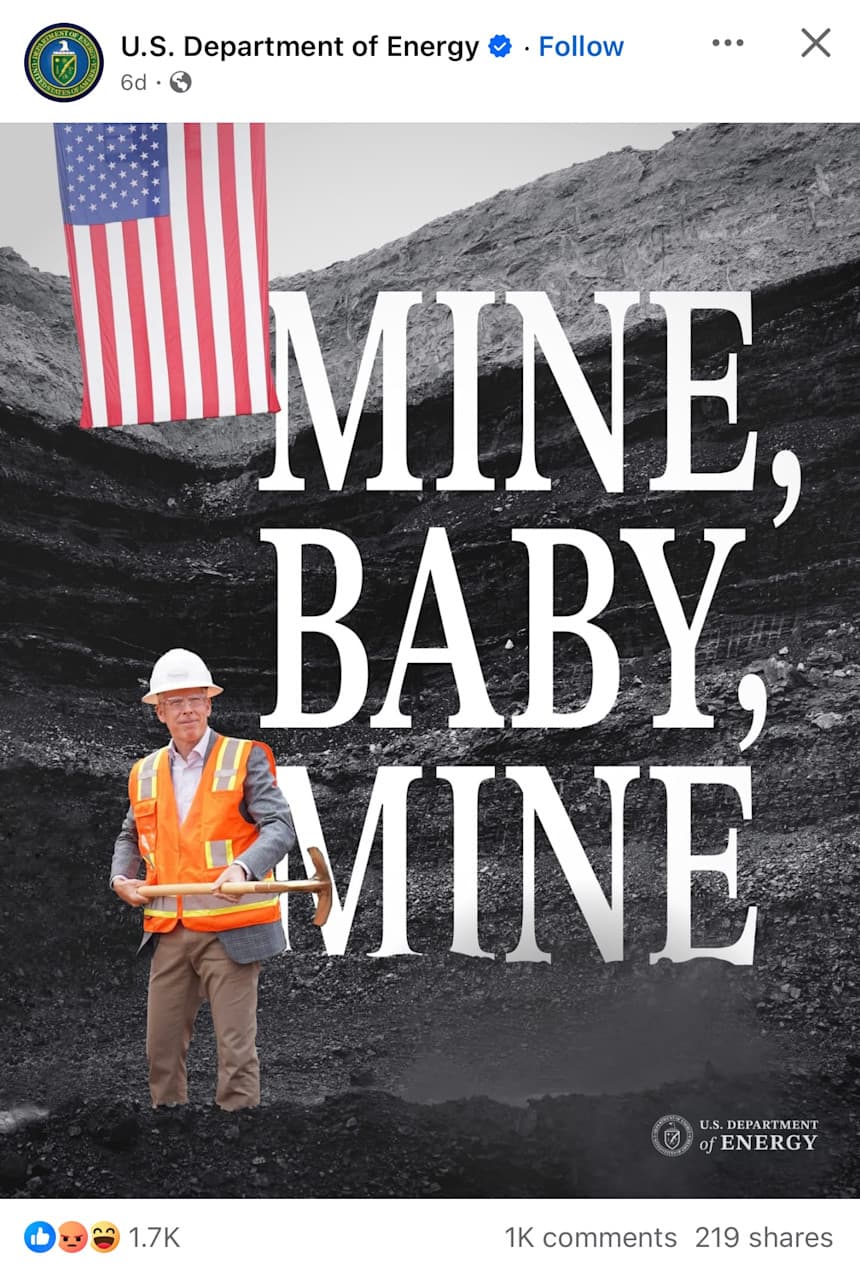

Mine, Baby, Mine

A real Facebook post from the U.S. Department of Energy that appeared on my own feed.

References and Extra Reading

A Battle Below the City by Cheryl A. Kashuba

History of the Pennsylvania Anthracite Region by L. Michael Kaas

Trump announces billions in investments to make Pennsylvania an AI hub by Jay Peters

Reinvigorating America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry and Amending Executive Order 14241 by Donald J. Trump — Executive Order

The multi-faceted challenge of powering AI — MIT Energy Initiative by Nancy W. Stauffer

Blackstone to invest $25 billion in Pennsylvania data centers and natural gas plants, COO says by Reuters

$26 billion in data center projects coming to central Pa. by Daniel Urie — Pennlive